Beilin Museum

Located beside the southern wall’s Heiping Gate, the Beilin Museum houses a fine little collection of steles and religious artwork from a variety of different dynasties.

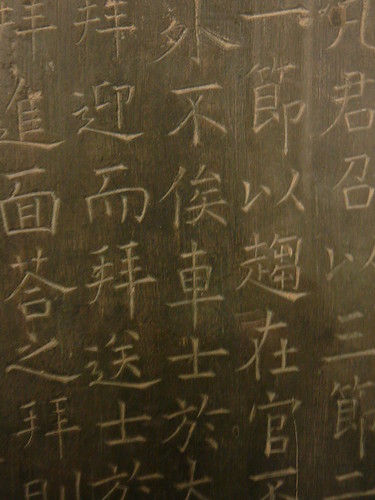

The steles—large, carved stone blocks—are spread through seven rooms. The first contains classic works of Chinese philosophy and ethics. The black slabs, one lined after another, puts one in mind of the Vietnam monument in Washington, DC.

The second features family memorials, records of foreign relations, ennoblements, land-grants, and writings recounting the good deeds of various religious leaders. The third displays poetry, especially impressive calligraphy, and various inspirational accounts of filial piety.

The forth room is the most interesting, offering up a grab bag of steles. Some are portraiture and landscape, others are memorials—one, for example, commemorating a peasant rebellion leader financed paid for by his peasants followers. Another from several centuries later is a warning from the Qing to similarly rebellious peasants.

The western wing of the museum is given over to sculptures and carvings discovered in and around burial sites. These include the elaborately designed tomb of Li Shou, a cousin of the then-emperor; massive tomb guardians in the shape of lions, goats, rhinos, and mythical creatures; and “pictoral stones” showing both fantastical imagery—dragons, ghosts, and anthropomorphized animals—as well as more mundane scenes such as hunting and harvesting.

There are also a fair number of Buddhist sculptures. When the religion arrived in China, such artwork was used to educate the illiterate about the faith’s teachings. The museum’s collection ranges from small household relics to large heavenly guardian statues.

The value of the museum’s pieces lies not only in the things themselves, but in the contemplation of how much care and effort—a lifetime of knowledge and craftsmanship—went into their creation. Viewing works so full of passionate labor, one comes a bit closer to understanding lives long past lived.

Yangrou Paomo

Chances are good that, if you’re a foreigner living in Xi’an, a local has probably taken you out for yangrou paomo. If not, it’s only a matter of time. The restaurants are everywhere; lining the streets of the Muslim Quarter, glimpsed down alleyways, even operating out of swank, high-end venues. Inside many city buses, posters advertising the wonders of Xi’an culture show the terracotta army, the Big Goose Pagoda, the Tang Dynasty show and a bowl of yangrou paomo.

This is the local dish and it’s marvelously simple: Bread, noodles, mutton, spices and broth. For the north Chinese with their traditions of horse riding and long distance hunts, the dish was both simple and filling. A Muslim influenced Silk Road dish, it is said to have originated in the 11th century, at the court of the Western Zhou emperors.

In the heavily touristed areas of the city—like Muslim Quarter—you’ll see yangrou paomo sitting in pre-made bowls (9 ¥), just waiting to have broth ladled into it. While this can be tasty, it’s not the customary way to eat it.

In the better restaurants (20 ¥), you’ll first be asked how many pieces of bread (bing) you want. One will be fine if you have a modest appetite, two will certainly fill you. Once your choice has been made, you’ll be handed the bread and an empty bowl.

What follows is a process of breaking the rounds of bread in half and ripping those halves into small pieces. Whereas a machine compresses the bread, ripping by hand keeps it soft and allows it to retain absorbency. The smaller the pieces are, the better they suck up the broth—and, as a friend insisted to me, if I didn’t tear the pieces up small, the cooks would take me for a country-bumpkin and withhold the choice meat slices.

While thorough ripping can take time, Chinese insist that the whole business can have a relaxing, almost zen-like quality. You become part of the cooking process.

Ripping done, the bowls are whisked away and returned several minutes later full of broth, vermicelli noodles, and slices of mutton. Served along with the meal is a spicy chili paste and sweet pickled garlic which can either be eaten on its own or mixed into the bowl.

This is kou tang (mouth soup); it is what you can expect to be served if you don’t specify otherwise. If this doesn’t quite appeal, several other options are available: Dan zou (walking alone) is a version where the broth, meat and noodles are served up with the bread, as yet still whole, on the side, ready to be dipped in. Gan pao (dry soaked) is the standard yangrou pao mo drained of its broth, but still soggy. And, most wonderfully named, is shui wei cheng (water besieged city) which is just your typical paomo bowl brimming with broth.

The best way to eat yangrou pao mo is to work around the outside toward the center. Since the bread is thoroughly soaked in broth, it is quite hot. Avoiding the center of the bowl bypasses the hottest portion and leaves the roof of your mouth intact, allowing you to enjoy Xi’an’s signature dish with the utmost satisfaction.

Banpo Museum

Banpo Museum is itself something of a relic. Old photos near the entrance, show the site in the early 50s, at the time of excavation. A few archeologists stand amid locals. Around them stretch empty fields. Now the place is surrounded by roads and buildings and getting there requires a long bus ride to the eastern suburbs, beyond the Chan River.

The museum displays the remnants of a 6000 year old village. Covered by a large warehouse building are the remains of numerous huts, identifiable by numerous stake holes in the ground. Wooden frames, subsequently filled in with mud and straw, were set in the holes.

Archeologists suspect that the Yangshao culture which inhabited the site was matriarchal (e.g. run by women). Female burial sites contain far more objects than male ones, leading researchers to believe that women’s position in the society was elevated.

In addition to these burial sites, archeologists have unearthed a great deal of pottery used to bury dead children. A number of storage pits have been excavated too, along with a portion of the deep moat which once surrounded the village.

Other buildings contain artifacts from the site and less obviously relevant displays such as animal fossils.

The nicest part of the museum, however, is the least historical part. Outside the main building is a large garden area full of peony flowers and reconstructions of the Neolithic huts. The whole place is in a state of quaint disrepair, but the upshot is that you find yourself able to sit in relative peace and quiet.

Chinese Calligraphy

How does one express his inner nature? How can we best judge a person’s soul? For the imperial Chinese, writing offered the window. Zhang Xu and Huai Shu, two Tang dynasty calligraphers, for example, would get liquored up and launch into shouting tirades as they performed their art. Zhang, it is said, would often use his hair in place of a paint brush. Not surprisingly, the two avoided standard writing styles in favor of freer forms.

Nowadays, when we think of Chinese script, we tend to separate it into Traditional and Standard. When confronted with the thought of learning the former, those of us unable to learn even the latter shudder. Yet both are merely a fraction of the range of characters once in common circulation among literate Chinese. What we think of as “written Chinese” is just kaishu style, the simplest of five possible scripts.

The oldest style of Chinese writing is zhuanshu, or Seal Script. Originating several thousand years ago, it conveys a sense of visual antiquity. The characters are long, narrow, insect-like, almost otherworldly. The impression is far more literal than other, more abstract scripts. It was the official writing style of the Qin dynasty.

Lishu script, or Clerical Script, followed. Much faster to write than Seal Script—and, therefore, more suited to use in bookkeeping—it retains some of the same elongated qualities as its predecessor.

The other three major scripts emerged concurrently during the Han. Two of these, caoshu (Running Script) and xingshu (Walking Script), are cursive versions of the clerical script. As the names suggest, caoshu is the more flowing and difficult of the two while xingshu moves between the two extremes of precision and wild abandon. Kai (Standard Script) is a further, squarer, less-stretched version of the clerical script.

Within a single style there are a range of techniques. Connoisseurs of calligraphy can rhapsodize about how the smallest action can alter the sense of a character. Whether one uses the edge of the brush or the tip, how long the brush is used before refreshing the ink, how much pressure is applied; the choice of both style and mode of expressing it speaks volumes about the calligrapher.

Yet, beyond reflecting the personality of the individual calligrapher, calligraphy is also a conversation between the present and the past. Great artists carefully study the examples of past masters. (Consider Wang Xizhi, the forth century scholar and “Sage of Calligraphy.” Not only was he a beautiful calligrapher in his own right, refining styles in a manner still emulated to this day, but he also labored to collect the work of many others, past and present. His most famous work is his preface to Literary Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion, a collection of poetry by artists he’d brought together.)

To appreciate and to produce calligraphy is thus both an individual and a collective act of the most surpassing subtlety and beauty.

No comments:

Post a Comment